The Enigma of Science Education

Chapters: | Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Next |

Awareness of natural phenomena enhances scientific thinking

- Teachers tend to overwhelm their pupils with formulas and laws whose context often remains obscure to the learner. This is why learners acquire a knowledge which they cannot transfer to their own reality. On the other hand when experiencing our natural world we encounter images based on laws of nature. Learning strategies aiming to make children aware of phenomena instinctively known to them can favour the transition from “implicit” to “explicit” knowledge and lead to scientific thinking.

The following is a report on a course of a mixed group of learners (aged 9 – 12). The course was specially designed to enable the younger pupils to experience different aspects of reality by acting independently. It was not of importance what a child – in the sense of Piaget – cannot learn at a certain age but rather which early predispositions in children are stimulated in a certain learning environment and how these abilities could be further developed.

The major task of the teacher was to assist the children and to allow adequate time for reflection.

The following questions and remarks were the starting point:

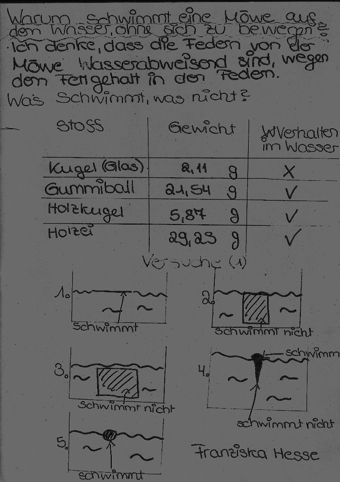

- Franziska is wondering why a seagull can sit on water without moving. Even a gigantic wave cannot overturn it.

- Julia has observed that some snails carry a house and some don’t.

- Katinka thinks that a duck can be a pet.

- Max pretends to be able to see in the dark.

In the following I am going to explain the process of clarifying and solving a problem by discussing the first remark: Why a seagull can sit on water without moving.

The following ideas and images were expressed:

Samantha (aged 12): I suppose a duck moves its legs under water in order not to sink.

Franziska (aged 12): Maybe the feathers of the seagull are water-proof because they contain a lot of fat.

Felicia (aged 9): I think that the seagull weighs so little that it can sit on water without moving.

Lukas (aged 11): Maybe the seagull doesn’t sink because one litre of water is heavier than “one litre of seagull”.

Erik (aged 11): There is air underneath its feathers – that’s why the seagull stays on the water surface.

Anna (aged 10): I think that it is swimming on the waves and is keeping its balance.

We here encounter six different opinions and none of them is implying scientific concepts such as density and buoyancy. I had the opportunity to let high school students (aged 14 – 20), primary school teachers and also university students to comment Franziskas remark on the seagull. Surprisingly most of them came up with exactly the same answers in almost exactly the same context. On the other hand if you ask students to define density they do know its definition. Many university students also use the term “buoyancy” but cannot explain what precisely is meant by it.

In the following phase children were asked to describe their experience when swimming in a lake or swimming pool.

The following remarks were given spontaneously:

- Our body is partially under water. The body occupies the place of the water. The water has “to give way” to the body.

- We move our hands and feet to shift the water.

- The shifted water remains in the pool and comes back to retain its original place.

- When you go out of the swimming pool using steps your body feels heavier as soon as you take the first step outside the water.

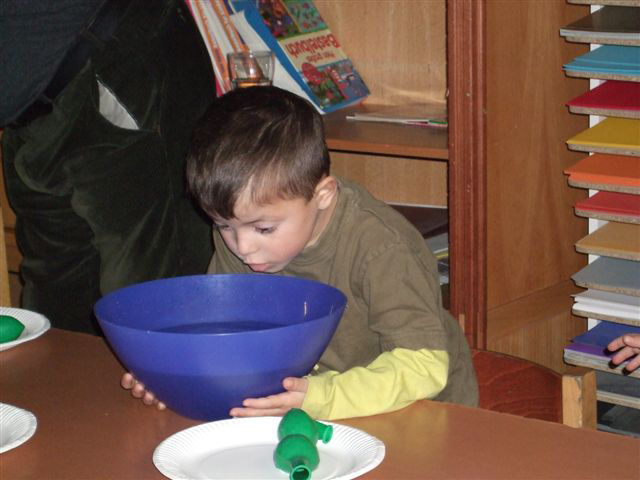

During the following lessons children had the opportunity to do several experiments and to justify their opinions regarding floating and sinking. They were provided with buckets of water, aluminium foil, balls of different material and size (glass, wood, metal) as well as plasticine, oil and fat, syrup and sugar.

Here is one example how the data was collected:

After the children had been busy doing self-designed experiments for some time they came to various conclusions. Here are some of their remarks:

- If you place, for example, aluminium foil flat on the water surface then it is supported by plenty of water. But if you put it vertically into the water then it has less water to support it. Therefore it sinks.

- If you place a flat piece of plasticine on the water it sinks. But if you form the same piece in a boat-like shape it swims.

- If you fold a fairly large piece of aluminium foil again and again it gets smaller and thicker and does not swim. But if you take the same weight of foil and make a ball out of it swims because a large part of it is under water and thus displaces more water.

- If the object displaces enough water the water forces the object up. That is why the seagull does not have to move.

- If you carefully pour half a glass of syrup into half a glass of water the syrup goes through the water and settles down because water has holes. But if you pour water into the glass of syrup it stays on top of the syrup because there are no holes in the syrup to let the water go through it.

These statements show clearly that the pupils were able to give up their original ideas concerning floating and sinking. Furthermore they constructed their new knowledge independently thereby acquiring new concepts. Apparently high school and university students, primary school teachers did not have the opportunity to construct their knowledge and therefore still offer the same opinions as a child of 9-12 years.

Chapters: | Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Next |