Lifelong Learning – Stimulating Knowledge

Chapters: | Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Experimentation

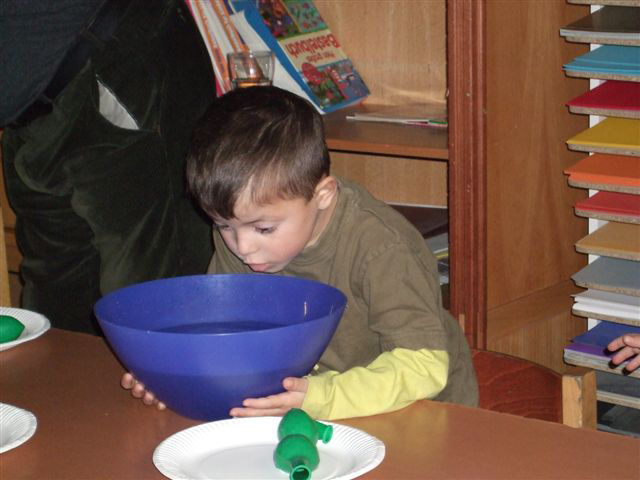

We asked ourselves how trees take up water – was it through the leaves or the roots? One child believed that plants would only “drink” water from their roots. “What do you mean?” I asked. “When you water a plant, you don’t water the leaves,” was the answer. Then we imagined how nature would look after heavy rainfall, and together we came to the conclusion that the leaves would not grow any thicker and the grass would look the same. We took the leaves into the common room, and I suggested putting drops of water on them so that we could watch and see whether they would gradually absorb them all the same. Each child was given a beaker of water, and in actual fact the drops did not penetrate the leaves, although they did make them glisten beautifully. Then we raised the question of which materials “drink” water and which do not. The suggested materials were paper, aluminum foil, a cotton towel, greaseproof paper and a chamois leather cloth, so we gathered these items and carried out an experiment. The children discovered that cotton can “drink” water, but aluminum foil cannot. By now they were almost sure that plants can absorb water through their roots and distribute it to the stem, branches and leaves, although they did not ask how the water can rise up to the tops of large trees.

This example is intended to give an impression of the endless variety of topics available and the possibilities for consolidating this knowledge over the next few days or in years to come. There are no right or wrong answers here; we are feeling our way, just as people have always felt their way further and further towards understanding phenomena that seem incomprehensible at first. We consider every solution put forward and test it together. “What do you mean?” is an important question that a teacher must always ask to prompt further explanation or reflection.

This example is intended to give an impression of the endless variety of topics available and the possibilities for consolidating this knowledge over the next few days or in years to come. There are no right or wrong answers here; we are feeling our way, just as people have always felt their way further and further towards understanding phenomena that seem incomprehensible at first. We consider every solution put forward and test it together. “What do you mean?” is an important question that a teacher must always ask to prompt further explanation or reflection.

Motivation

One kindergarten teacher who took part in one of my training events came to the realization that it can be very easy to strike out in new directions if you adjust your point of view – even just a little. In this case, the children were given dried beans, juniper berries, peas, lentils, corn kernels and raisins and were tasked with comparing them, naming their properties – and expanding their vocabulary in the process, and learning how to estimate proportions in size and quantity.

Many of them had never heard the word “raisin” before. Two of the children debated whether raisins and grapes had anything in common. The kindergarten teacher immediately intervened and explained that “A raisin is a dried grape.” This action was assessed in the discussion later on, and in a subsequent interview the kindergarten teacher said: “It suddenly became clear to me that this is what I have always done. I gave the children a direct, explanatory answer to a question. Now I realize that giving children such direct answers to their questions stifles their curiosity. However, responding with the counter-question ‘What do you mean?’ encourages them to think about the question more deeply and to come up with their own thoughts about a phenomenon.”

This realization is a prime example of lifelong learning and the opportunities that are open to us if we, as adults, discover the world together with the children.

Salman Ansari: Lifelong Learning. An Essay in: Credo (LGT Journal on Wealth Culture) XVII 2013, P. 15-17

Salman Ansari was born in India in 1941 and has worked in Germany since the 1960s. A graduate in chemistry and an expert in education, he has taught at the Odenwaldschule and is now in great demand as a lecturer. He recently published a book entitled “Rettet die Neugier! Gegen die Akademisierung der Kindheit” (“Give Curiosity a Chance! Arguments Against the Academization of Childhood”).

Chapters: | Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 |